Despite this, only one American was shot for desertion in the whole war. His name was Eddie Slovik.

Troubled Beginnings

Eddie Slovik didn’t have an easy upbringing. Born in 1920, he grew up in poverty during the Great Depression. As a child, he spent time in a reformatory before graduating to prison time as a young man.

Eddie Slovik in 1920

Called up to the army in 1944, Slovik trained as an infantryman. He was still training when the Allies invaded Normandy in June 1944, beginning the year-long campaign that would end the Second World War in Europe. When he finished training, he was shipped out to Europe, arriving in France in August.

U.S. troops disembarking on Utah Beach, 6 June 1944. Normandy

landings

Slovik was small and nervous, hardly the ideal combat soldier. But America’s more prestigious forces drew off the best recruits, leaving the infantry to take what they could get. What they got was Eddie Slovik.

Into the War

The chain of events leading to Slovik’s death began before he even reached the fighting front. Slovik and his friend, John Tankey, were among thirteen replacements sent to cover losses in Company G, 109th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division. The division was attacking the French town of Elbeuf, held by a small group of Germany’s fanatical SS troops.

Operation Overlord (the Normandy Landings)- D-day 6 June 1944

Commando troops coming ashore from LCIs (Landing Craft

Infantry).

The conflict in northern France was characterized by this sort of fighting. The Germans clung tenaciously in place, using terrain to make life difficult for the Allies. A greater weight of manpower and resources meant that the Americans kept advancing, but often at a terrible cost.

Slovik and Tankey had not even reached their unit when the trouble began. In the darkness outside Elbeuf, the replacements came under fire from German artillery. They leaped for cover and began frantically digging foxholes, while the air around them was filled with terrifying noise and the blast of exploding shells.

German SS troops advancing past abandoned American equipment.

By the time dawn arrived, Slovik and Tankey were alone. The others were either dead or had moved on in search of their unit.

Desertion

Slovik and Tankey had seen all the combat they wanted to. Rather than continue towards the fighting, they found a group of Canadian military police, the 13th Provost Corps, and attached themselves to the unit. At that time, the job of the 13th was to roam the French countryside, putting up notices explaining the martial law applying in Allied-occupied zones.

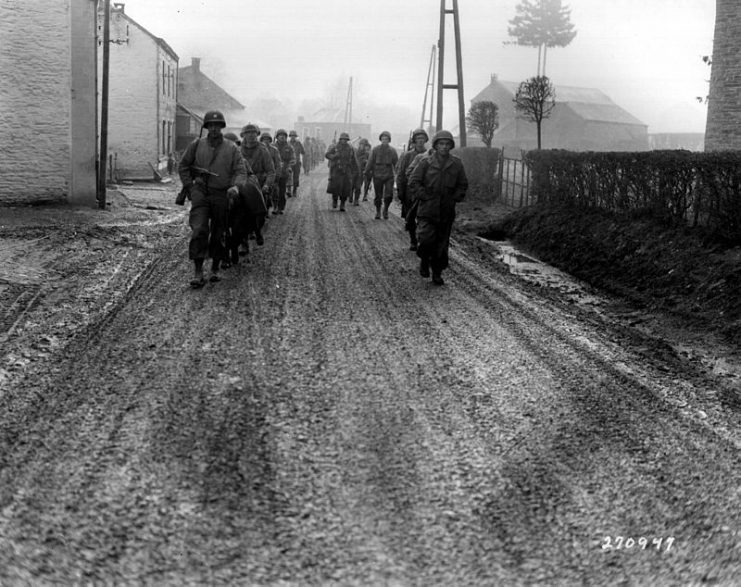

II Canadian Corps troops of the Régiment de Maisonneuve

advancing along a road

Slovik and Tankey made themselves useful to the Canadians as they traveled through France and then Belgium. They traded for luxuries on the black market and found French girls for the MPs. They never explained how they came to be detached from their unit and the Canadians didn’t ask. Through a policy of don’t ask, don’t tell, the deserters and the military policemen established an ironic yet comfortable arrangement.

Back to the Regiment

In October, Slovik and Tankey decided to return to their unit. This proved easier than expected. The first fighting on the German frontier had shaken the 28th Division. In the confusion that followed, officers were willing to accept the men’s return without asking too many questions or pressing charges.

Men of the 28th Infantry Division march down a street in

Bastogne, Belgium, December 1944. Some of these men lost their

weapons during the German advance in this area.

Tankey returned to combat, where he was wounded a month later. He missed most of the rest of the campaign. Slovik lasted only a few hours. Assigned to a rifle platoon by Captain Ralph Grotte of Company G, he soon turned around and walked away from the front. Tankey tried to stop him, but it was no use.

Within weeks, Slovik had turned up again. He told how he had warned Grotte that he would desert if sent to combat again. He seemed to think that this would get him off the hook. On the 26th of October, he was imprisoned at the divisional stockade at Rott.

United States Army soldiers supported by a M4 Sherman tank move

through a smoke-filled street in Wernberg, Germany during April

1945

Trial

By November 1944, a large part of the American army was bogged down in the Hurtgen Forest. As the losses mounted without progress, discipline deteriorated.

Slovik’s court-martial began at 10 am on the 11th of November. By 11:40, it was all done. The officers wanted to set an example. Slovik was to be dishonorably discharged and executed by a firing squad.

A U.S. halftrack of the 16th Infantry Regiment/1st U.S. Division

in the Hürtgen Forest, 15 February 1945

Despite the outcome, Slovik wasn’t worried. Hundreds of soldiers had deserted and many had been condemned to death. But while the Army shot men for other crimes, it hadn’t executed a deserter since the Civil War.

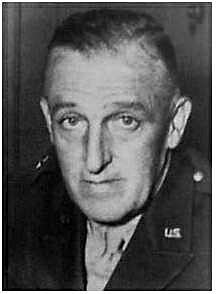

Slovik’s case now went to General Norman Cota, a courageous frontline commander with little patience for either psychiatry or deserters. On the 27th of November, Cota approved the death sentence.

General Norman Cota

Approval for the execution still needed to come from General Eisenhower, the supreme commander of Allied forces in Western Europe. Eisenhower’s legal staff were amazed to learn of the precedents relating to the case, namely no executions for desertion since 1865.

But by the time the case reached Eisenhower in December, desertions had soared again, thanks to the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower felt that he needed to set an example. On the 23rd of December, he confirmed the judgment. Slovik would be shot.

Eisenhower speaks with men of the 502nd Parachute Infantry

Regiment, part of the 101st Airborne Division, on June 5, 1944,

the day before the D-Day invasion.

Execution

On the morning of the 31st of January 1945, Eddie Slovik was brought from the stockade to the mining village of St. Marie aux Mines. The ground was draped in a shroud of snow.

Slovik, resigned to his fate, tearfully handed letters for his wife to the chaplain. The charges against him were read out. He was then strapped to a pole and had a hood placed over his head.

In keeping with a suggestion from General Cota, Slovik was shot by a dozen men of his own regiment. Veterans of the fighting that Slovik had fled, they showed no qualms about their work. On the order of an officer, they shot the unmoving Slovik. In keeping with tradition, one rifle carried a blank. All the other eleven hit.

Slovik didn’t die immediately, but by the time the medical officer had checked on him and the riflemen had reloaded, he had passed away.

Cota and Eisenhower had made their points. Deserters could not count on mercy while their comrades faced the horrors of war.

Page last revised

02/13/2019

Page last revised

02/13/2019